What does the 1980’s crime wave in New York City and Australian Construction Sites have in common?

The answer to the purposely cryptic title of this blog is simply:

Broken Window Theory

Enforcing PPE on site can often feel like sweeping leaves on a windy day. Decades after hard hats, long sleeves, long pants, steel caps, and safety glasses became the industry standard, we are still pulling people up on site for not complying.

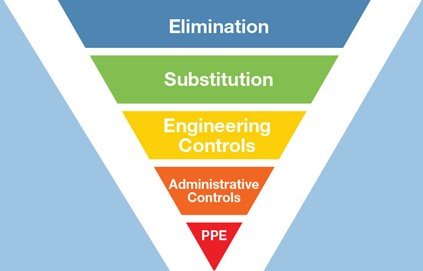

PPE is the least effective control in the risk controls hierarchy. It is almost the lowest hanging fruit and easiest thing to ‘pick on’ in a safety inspection. This duality causes a level of resentment throughout the industry, where workers often believe that the least important aspect of safety receives a disproportionate amount of attention. However, the research and studies show that the value of PPE goes far beyond the immediate protection it gives workers. In fact, the value is in creating a safety culture. Refer to the previous blog “Culture eats strategy for breakfast” for a more in depth look at the power of organisational culture.

Now to 1980’s New York City, where the term broken window theory was born (I swear this comes back around). The 1980’s in NYC saw a dramatic rise in violent crime across the city. The crime was so widespread that the police department and mayoral office had run increasingly out of ideas and resources to deal with the ever-worsening issue. The election of a new Mayor and the appointment of a new Police Chief looked towards the field of academia to a new approach.

The Broken Windows Theory, proposed by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling in 1982, provides insights into how small signs of disorder can escalate into more significant problems. Imagine a vacant building with a few broken windows. If these windows remain unrepaired, vandals are likely to break more of them over time. As the situation worsens, vandalism becomes normalized, and the frequency of such acts increases.

Former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani applied the Broken Windows Theory to policing. By addressing minor signs of disorder (like graffiti and fare evasion), he aimed to prevent more serious crimes. The visible sense of order and cleanliness discouraged criminal activity and contributed to a safer city. This is evident in transformation of NYC throughout the 90’s into a far safer city.

A construction site where everyone follows the basic rules of PPE compliance, and no one turns a blind eye, will inherently create a safety culture on the site and avoid small non-compliances snowballing or escalating into larger non-compliances. The culture counts. Especially in construction, where the people performing the works have the greatest influence and expertise into the safety of the works performed. As construction professionals, often the most valuable contribution we have to safety is leading a safety culture by caring about the little things.

Safety culture drives safe behaviours. When a new worker rocks up to a site where only half of the people were in complaint PPE vs rocking up to a site where everyone is PPE compliant, their attitudes and behaviours will be largely set from that point on. As humans we mould our behaviours to the status quo in an effort to fit in. Experiments have shown that subjects will give a clearly wrong answer to a question if everyone else in the group does the same (honestly, read up on the Asch Conformity Experiments). Our crushing need to fit in causes a compounding effect where small non compliances can snowball into a culture of ‘who cares’. Equally though the same snowball effect can result in a safety culture where everyone ensures that everyone goes home safely at the end of each day.

Safety culture isn’t just a buzz word or something without tangible value. The BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the gulf of Mexico’s investigation concluded that the largest ever oil spill was the result of poor Safety Culture. There were no issues with the paperwork, it was a safety culture that had been allowed to deteriorate over time, costing $61.6 billion USD, and leading to the CEO Tony Hayward stepping down.

Safe outcomes are a product of a safety culture, and this is everyone’s responsibility. However, it is driven from the top down, and our industry relies on leaders who care deeply about safety.